One of the questions I hate the most is “What kind of books do you read?” It’s a question that immediately makes me wonder why they’re asking, and how to answer that would best throw a wrench in those expectations.

I’ve never used the Poll functionality in Substack before, so let’s see how this goes.

These days, I just say, “anything I feel compelled to finish.” I’ve gotten ruthless with my reading, dumping even famous authors’ works 50 pages in, with no regrets about sunk cost. I want to build up my instinct for what makes a book sag, and that involves paying attention to my behavior and emotions as a reader. But beyond that, I have absolutely no restrictions. I read fiction and non-fiction, literary and commercial and everything from leadership development to poetry and fanfic, and I read work by emerging writers as part of critique groups as well. So a book has to stand out for me to feel compelled to finish it.

As part of one of my groups, our instructor (Jacob Ross) said something recently about what makes some books stand out. It was: “the writer is unafraid.”

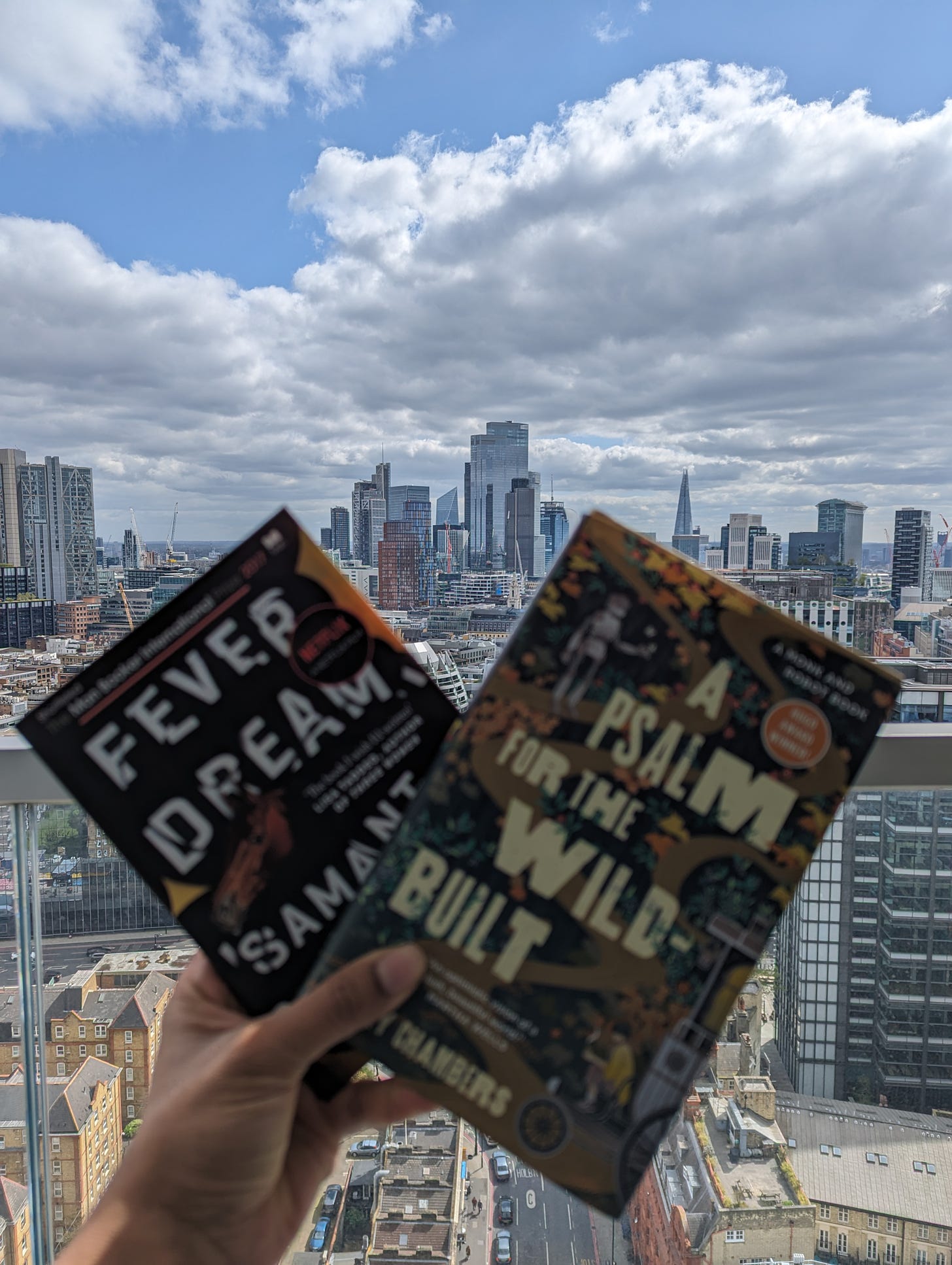

Two books I read recently (courtesy of recommendations from two subscribers here) demonstrate that.

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin

After a series of unimpressive thrillers claiming to be written from the perspective of an unreliable woman narrator (aren’t we tired of this trope yet?) I wasn’t expecting to be so blown away by this book. I definitely don’t recommend it to new mothers, but it’s a masterclass in writing speculative fiction that feels utterly real, and climate fiction that isn’t the least bit preachy. I also love the blend of ancient mysticism and modern pragmatism that infuses the novel. I’m glad that we’ve collectively gotten over the idea that art and politics need to be separated, but it’s rare that I see science and religion so well-blended too. There are cars, and there are shamans who transfer souls.

A Psalm for the Wiid-built by Becky Chambers

This could not be more different than the first book in tone, but addresses the same underlying question–what are the ramifications of late-stage capitalism on a planet and its people (and its robots)? I had absolutely no idea what I was getting into with this book, whose first line is: “If you ask six different monks the question of which godly domain robot consciousness belongs to, you’ll get seven different answers.” Again, the blend of ancient (tea monks) and modern (robots) is seamless (I’ll get to why that’s important in a minute). But here, a genderless tea monk known only as Dex questions their purpose, and it is a robot (built for a purpose by humans) that questions why they need one.

Here’s why it’s important that the writer is unafraid. In college, I studied Jonathan Frazer’s The Golden Bough, which in addition to misunderstanding a whole lot about religion generally, proposed a thesis that “mankind's understanding of the natural world progresses from magic through religious belief to scientific thought.” (Wikipedia) This is an imperialist perspective, one that effectively declares native shamanistic perspectives to be primitive and barbaric, and that religious structure offers the barest civilizing influence, but scientific thought is the ultimate goal for any people or culture.

We were taught to critique this perspective (which is already progress from the last century where this would have been accepted as fact). But even in the class of young people at a very liberal institution, this perspective was dominant. For justice to prevail, scientific thinking, objectivity and reason had to triumph over religion, perspectivism and emotion. I wasn’t the only STEM student taking the class, and there was a sense of importance and privilege we shared at the time. After all, once we graduated, the scientists would be paid more. Clearly our path was better.

It’s one reason I’m actually glad about the AI revolution. While creatives are (rightly) up in arms about what this means for their already diminishing access to wealth, now a lot of STEM folks are realizing that their value to a capitalistic society is diminishing too–what else do we have to offer? Who are we, really, and what are we for?

Writing is and has always been one of the most powerful political acts, and fiction has always engaged with the terrors of our time. Only a fearless writer can imagine a world that carries some of these “What if’s” to their most extreme conclusions, either pointing to the cliffs we’re headed towards, or the salvation that might be possible, if we, too, were unafraid.

I'm glad you enjoyed Fever Dream. It also blew my mind :)