On giving all your perfect imperfections

Did John Legend know the mortifying ordeal of sharing drafts?

One of the most painful but necessary lessons I ever learned was the impossibility of perfection. Growing up with a school and broader culture where anything short of a 100% score was a failure, I was lucky enough to be raised in a home where giving your all to any task was necessary, but the outcome was irrelevant.

That’s not to say I didn’t sob my heart out any time I could have got a perfect score but made a careless mistake. Playing competitive sports helped to inure me to the sting of loss (if you don’t lose, you don’t learn). Going to college and being graded on a curve made things worse for a while (what do you mean, I can give my all and still only get a B?) And, of course, corporate life with its system of reviews and promotions is a constant source of anxiety even to the most well-adjusted person.

Now add in the life of a writer. There is NOTHING more terrifying to a creative person than sharing a draft and having negative feedback come in and destabilize your very sense of self. (That’s my SOUL on the page, don’t they know that?)

Ten years ago, when I got feedback that was even the slightest bit negative, I would either go on the defensive or attack right back. It wasn’t a good look, and it wasn’t helping me grow. A manager kindly sent me to a course on giving and receiving feedback, which completely changed my outlook and my life. These days, I like to think I’m known for being really open to feedback, and to giving it pretty liberally too. Here are some of the things I’ve learned along the way.

1. Giving feedback: sandwiches aren’t healthy

Google gives a pretty good roundup of why the “feedback sandwich” of inserting your constructive feedback between two compliments doesn’t work. Instead, I try to do a two-parter: what’s working well, and what’s not working well. I spend a long time outlining not just what’s working well, but why it’s working, what’s the underlying skill the person has grasped that’s a superpower they should lean on. With what’s not working well, I frame it in terms of the problems I encountered, as one person with one perspective. It’s not something that’s objectively “wrong” with the text / work. I try (but sometimes fail) to avoid jumping to how I would solve it.

2. Receiving feedback: clarify first, solve later

My promised fantasy novel is actually something I’ve been working on for years. A long time ago, a writing coach gave me the following feedback on my synopsis:

Here, the conflict for your protagonist arises from her discovery of an enemy nation’s interpretation of past historical events. Remember what I said earlier how the strongest conflicts are often visceral ones, such as family bonds? It’s going to be hard for your readers to feel deeply engaged with a character who’s mostly upset about historical details.

At the time, I felt (but didn’t give in to) the urge to explain, to defend, to say anything from “But don’t you see, those historical events completely changed their sense of identity and family, making them furious about all the lies and hypocrisy and…”

I also felt (but didn’t give in to) the urge to dismiss, to attack, to say that a white male editor was unlikely to understand the generational trauma caused by mere “historical events” or that genocide wasn’t a “historical detail.”

Instead, I took a step back from the novel and came back to it after a break, and understood exactly what he was saying. Stories aren’t about the universal, they’re about feeling the universal through the particular. Once I got that, I knew how to do what I meant to do, but better.

3. Giving your all: the game, not the victory

There is this thing that sometimes happens on the court. When you’re up against a player or team who’s vastly better than you or very close to victory, there’s a temptation to give up and get it over with quickly. “No matter what I do, I’m not going to win, so why waste energy?”

The “fail fast” part of our brain has kicked in, trying to cut our losses.

In the movie Challengers, Tashi offers to give her number to whichever of Art and Patrick wins the game the next day. Art immediately deflates, because he has never yet beaten Patrick. Tashi says, “You can beat him. You should beat him.”

Of course, Art doesn’t. He doesn’t get that Tashi doesn’t actually care who wins, she just wants to see him give his all for “some good fucking tennis.”

The real kicker isn’t loss, it’s regret. It’s knowing you could have done better, but didn’t. You could have put yourself out there, lived the rivalry and the camaraderie, let the fact that others are better push (challenge) you, but you didn’t.

4. You can’t please everyone; don’t try.

Early in my writing career, I joined a bunch of critique groups. People would give tons of feedback, both micro and macro, sometimes in alignment with each other, but often the feedback was contradictory. It would be “more dialogue” and “less dialogue, more interiority,” “X’s character doesn’t resonate with me” and “X is my favorite,” “the ending is perfect” and “the ending is an anticlimax.”

At first, I’d try to do some stochastic weighting of the feedback based on the giver’s past successes or my estimate of their own writing. But just because someone can write their own stories doesn’t mean they know how to read or edit yours.

At work, I learned from extensive presentations to execs that they will never share an opinion, that asking for feedback is more likely to get you drive-by comments on distracting color choices than on your content (which they weren’t paying attention to). Trying to accommodate everyone’s feedback just made my work… soupy.

Work that’s opinionated won’t have a wide readership. And work that’s popular is usually simple. The key is to know what you’re going for, and stick to it.

5. Find your friendlies. Actually let them help you.

The key to growth is finding those people who know you’re not perfect, but believe in you anyway. My editor, Caroline, remarked on an in-progress work that she found a couple of side characters to be a bit one-dimensional. I failed to follow Rule 2 and tried to explain what I was trying to do with them, and she said, “I get it— and I see you’re doing what you set out to do, as always, very skillfully… I think I’m craving more dimension in part because your other characters are so very complex and rich.”

I love complex ensemble stories. Do most stories these days feature just one or two protagonists with dimension and relegate everyone else to the sidelines? Sure. But I want more out of the story, and out of myself. I think that a lot of our societal problems come down to our addiction to a single perspectival frame that closely matches our own, and that we need to get out of the narcissism of first-person YA that prioritizes a single, ephemeral voice.

There is nothing more valuable than someone who knows the journey you’re on and is willing to walk with you on it. But society tends to pit people like that against each other as competitors, rather than collaborators.

Below is a photo of “women of a certain age” in tech. We are a rare and special breed, and there is immense power in the fact that we are smiling like this at our workplace.

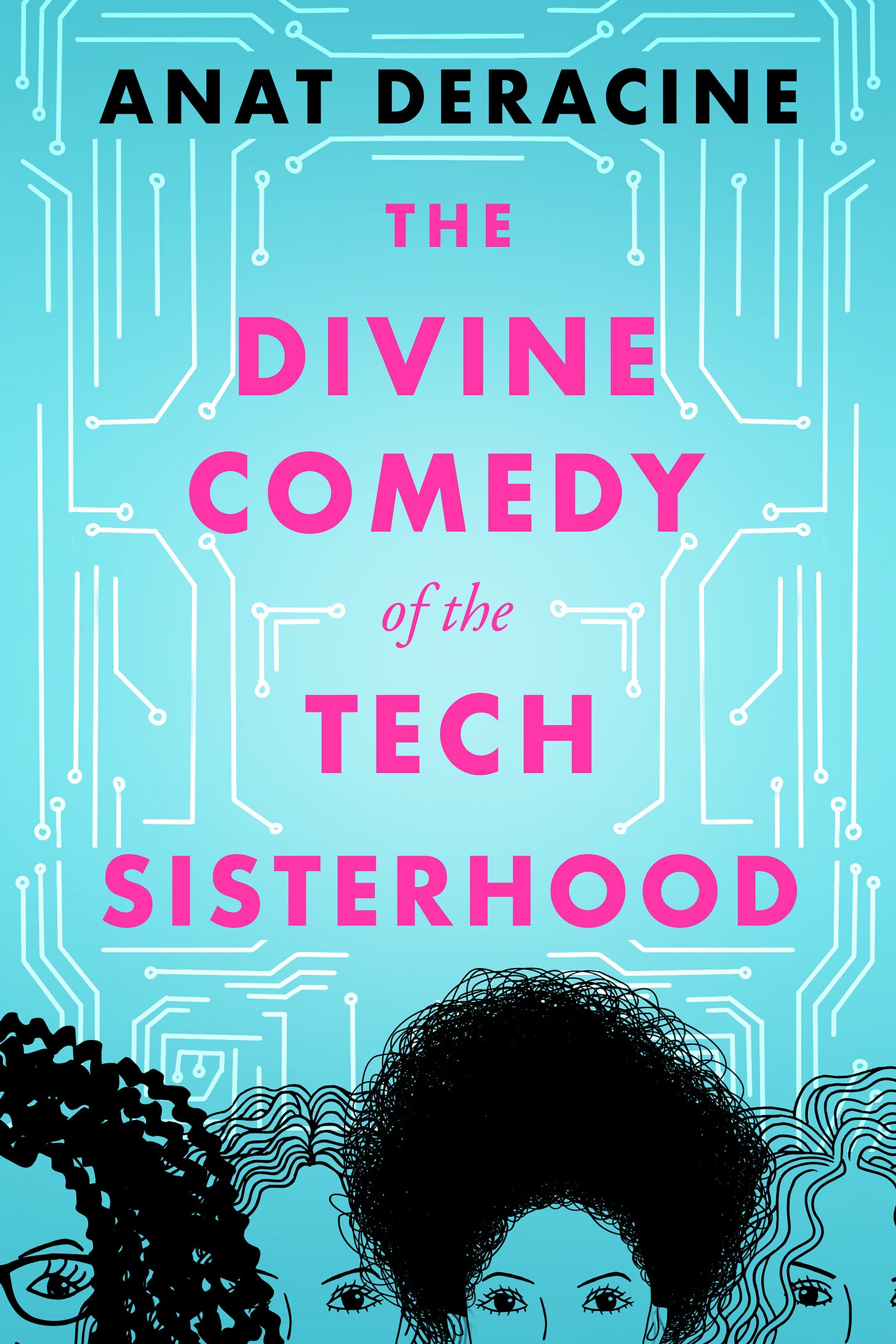

A few years ago, when I wrote The Divine Comedy of the Tech Sisterhood, it had the following passage that now seems prescient:

“Have you guys told your people that you’re in this group, talking through your problems?” Julie asks.

“No, why?”

“Well, when I was at my worst — ” she looks at you meaningfully, “ — I thought I was completely alone. I’d burned so many bridges, I’d been careless, and… it was the first time I’d ever felt helpless. There’s something that’s odd about being, well, being us, being survivors, and feeling helpless. We assume that if we couldn’t do it, nobody else could. Because we’re strong and we know it. Your reports probably think you’re just as powerless as they are. Just as alone. I think it would comfort them to know that you’re part of something bigger, something that cuts across companies and cultures. That you’re not just one lone woman trying to buck the system.”

BTW, if folks want to read the rest of the story and don’t want to deal with the Medium paywall, don’t worry. I’m planning to bring it out soon as an ebook and in paperback, and am happy to send a free copy (either format) to subscribers who want it. If you have thoughts on the cover, here are some drafts the designer and I are considering. Feel free to comment with your thoughts!

The faces at the bottom of the first one grab me.

For feedback, one great piece of advice I got a long time ago was that the feedback is pointing out the problem. It is up to you to find the right solution. Consider the fixes your peers suggest, but always take a step back and look for the problem their suggestions are pointing out, then determine the best fix.

You do that in your example, but I think it is worth calling out explicitly.

I am drawn to the first one! Couldn’t explain it, especially given that orange is usually my absolute cup of tea….which means it’s guy-level stuff and therefore Very True! ;)