Every writer, without exception, wants to write something that keeps the reader hooked till the end. There are endless books and classes that teach you how to tell a great story, that remind you to ratchet up the tension, raise the stakes, create urgency with a ticking clock, and torture your characters to keep the reader up all night turning the page.

But, as Lee Child says, all of these solutions are like recipes for baking a cake. And creating suspense is not like baking a cake.

“How do you create suspense?” has the same interrogatory shape as “How do you bake a cake?” But… “How do you bake a cake?” has the wrong structure. It’s too indirect. The right structure and the right question is: “How do you make your family hungry?”

Now, I read this advice a long time ago, but wrestled with putting it into practice. Because, in real life, you don’t actually try to keep your family hungry for hours. I can’t even tolerate being hungry for ten minutes, so I’m not exactly skilled at delayed gratification.

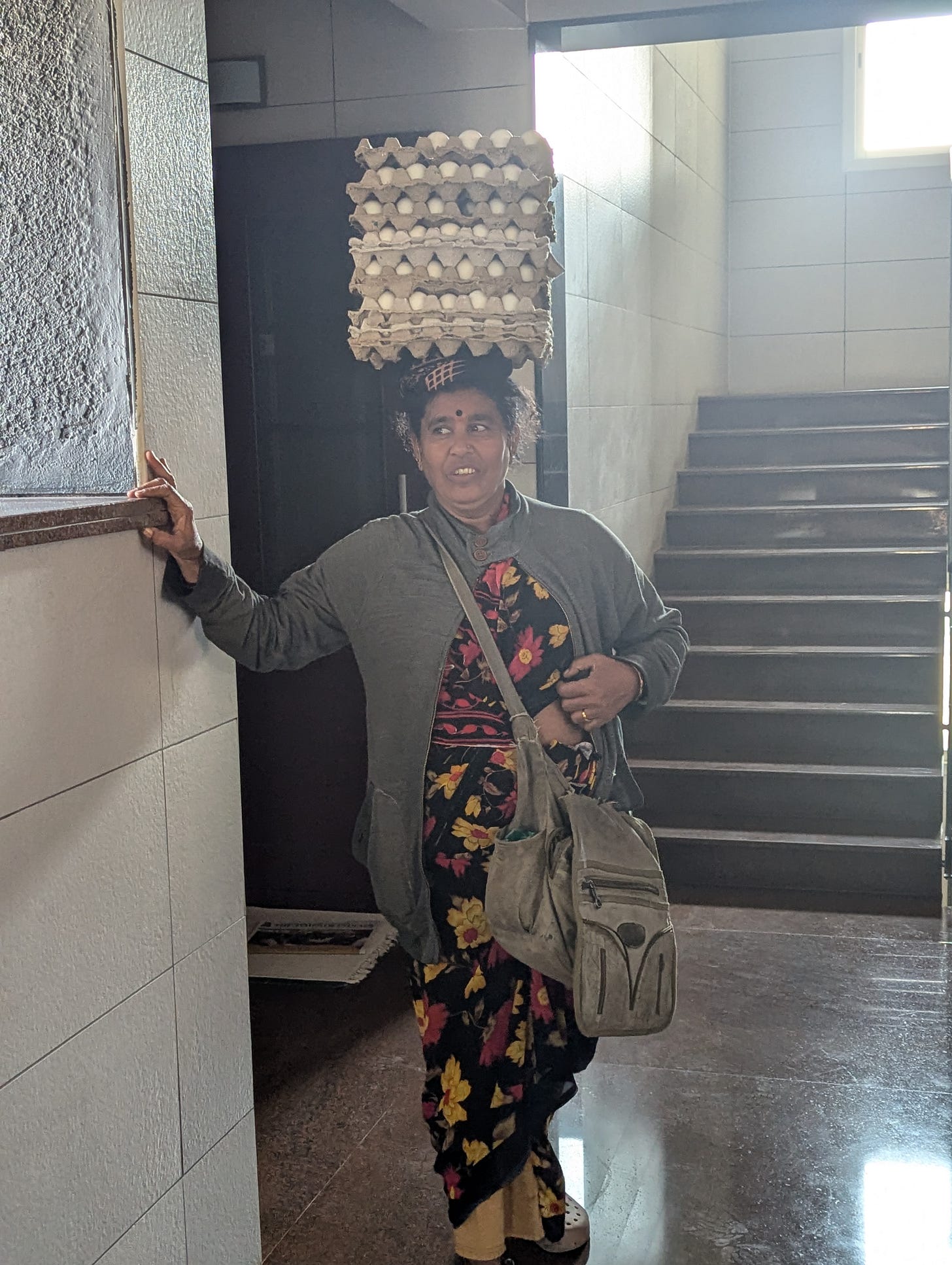

Then, a few weeks ago, I had a revelation. A coworker of mine was stressed out, but the source of her stress was vague fear—a state of being a lot of people have been getting used to since the U.S. election. To get her to relax, I told her about a woman in India whose job is to carry eggs to all the residents of a fourteen-story apartment complex. She climbs down the stairs with the eggs on her head.

I told my coworker, “Now, that’s a stressful job.”

She disagreed. “I’d rather carry the eggs! In the worst case, I might break some eggs, and I’d have to clean it up and deal with angry customers for a day. I’m stressed about invisible eggs!”

(To be fair, this woman doesn’t seem at all stressed about the eggs).

It got me thinking about that idiom, “the elephant in the room,” and about how oppressive a room can feel when something important and pivotal is unstated. It made me realize: that’s the tension I want readers to feel, that the next sentence, or the next line of dialog, or the next page is going to set off catastrophic consequences. Now, while some expert authors can create that sense of oppressive atmosphere without ever making a specific, credible threat, I figured I would start simpler.

Which took me to soap operas. I watched a lot of daytime soaps as a teenager (oh, Eden Riegel, you are still in my thoughts). Let’s just say it: I was addicted. I sometimes skipped class to come home for an early lunch, when I could simultaneously watch All My Children and Days of Our Lives. To carry a soap opera through years and years, you need to master tension. But the viewer won’t feel the tension unless they can also see the Rube Goldberg machine of past events. To understand why a line like “Shattered dreams are shattered dreams. Doesn't matter how or why. They're still lying in pieces on the ground.” can break your heart, you would need to understand not just years of backstory on one character, but on every character, to feel how it lands.

In other words, broken eggs are just broken eggs. But if carrying eggs on your head was an Olympic sport, and the character had trained to do it since childhood, despite poverty and injuries, to impress her idol, only to have the eggs knocked off her head because of a careless mistake by the only person she’s ever loved, then you watch the character carry those eggs while sitting on the edge of your seat, because you know how much it will matter if the eggs break.

So, how do we do this as writers? How do we expose the Rube Goldberg machine without hitting people over the head with recaps as soap operas do? Strangely, a technique I use at work to decrease tension has taught me a lot about how to increase it in my writing.

I am frequently in large meetings where each person comes in with a different perspective, information or agenda. As a conversation proceeds, I watch everyone’s faces closely. I can usually tell when people are starting to tune out because one person has gone on too long, or when someone doesn’t know what a particular technical term or acronym means. I’ve also usually done my research to know what agendas exist in the room, and where any points of conflict might be. To make sure everyone can participate fully, and to make the conversation as productive as possible, I do the following things to make the elephant (or the eggs) more visible:

Pause people when they run on too long.

Stop to explain terms that might not be familiar to everyone.

Start by laying out my own information, perspective and agenda, e.g. “Here’s what I know, I’m here to figure out how to solve problem X, and I need team Y’s help because I don’t know anything about subject Z.”

Bring out hidden information and perspectives even when they differ from mine, e.g. “I see this as a Venn diagram, but I know T sees it as a data cube.”

Lower the stakes by making it clear what the consequences of failure might be, e.g. “If we don’t get this done by the end of the week, we can postpone until next week.”

And then I go home and reverse all of those things when writing fiction.

Give the antagonist control of the narrative; don’t let the protagonist get a word in.

Let the protagonist flail around in uncertainty, with all they don’t know or understand.

Make other people’s perspectives perfectly clear to the reader, but opaque to characters, e.g. via telling the story in multiple points of view.

Hide information and agendas from the protagonist, e.g. so they are completely blindsided when someone close to them has secretly hated them all along.

Raise the stakes by never making it clear what the consequences of failure might be, so that the protagonist conjures up all sorts of invisible eggs to stress out about.

Ta-da! Tension. And you didn’t have to miss a meal to do it.