I am the height of Lee Child’s armpit. I am in love with Attica Locke’s voice. I am sitting in the lobby of The Old Swan Hotel in Harrogate, where Agatha Christie famously disappeared to in 1926. It is barely noon, and I have done more things today that terrify me than I have all year.

This morning, as I walked to a coffee shop, I found myself behind a very, very tall man. I knew immediately who he was, since I’ve come to Harrogate to see him, after being awed by his masterclass on writing at BBC Maestro. He was oblivious to my short presence behind him. I said, “Excuse me. Aren’t you Lee Child? I wanted to say thank you — you’ve changed my life.”

He was utterly gracious, and exactly as advertised. Large hands with a strong grip, clipped voice, cigarette dangling from his fingers. Kind eyes with crow’s feet. High on that interaction, I went on to the coffee shop.

Since I was early, I got a table. Others, arriving later, were not so lucky. A woman I recognized as a famous literary agent arrived and was turned away when she asked for a table for two. I waved her over. “I’ll be leaving soon,” I said. “Why don’t you take a seat here until then?” We got to talking, and she asked me to submit my book to her.

I finished my coffee. Her client arrived, and I left them to talk. Before I could overthink it, I followed up, sending her a query. Then, I collapsed into a lounge chair in disbelief.

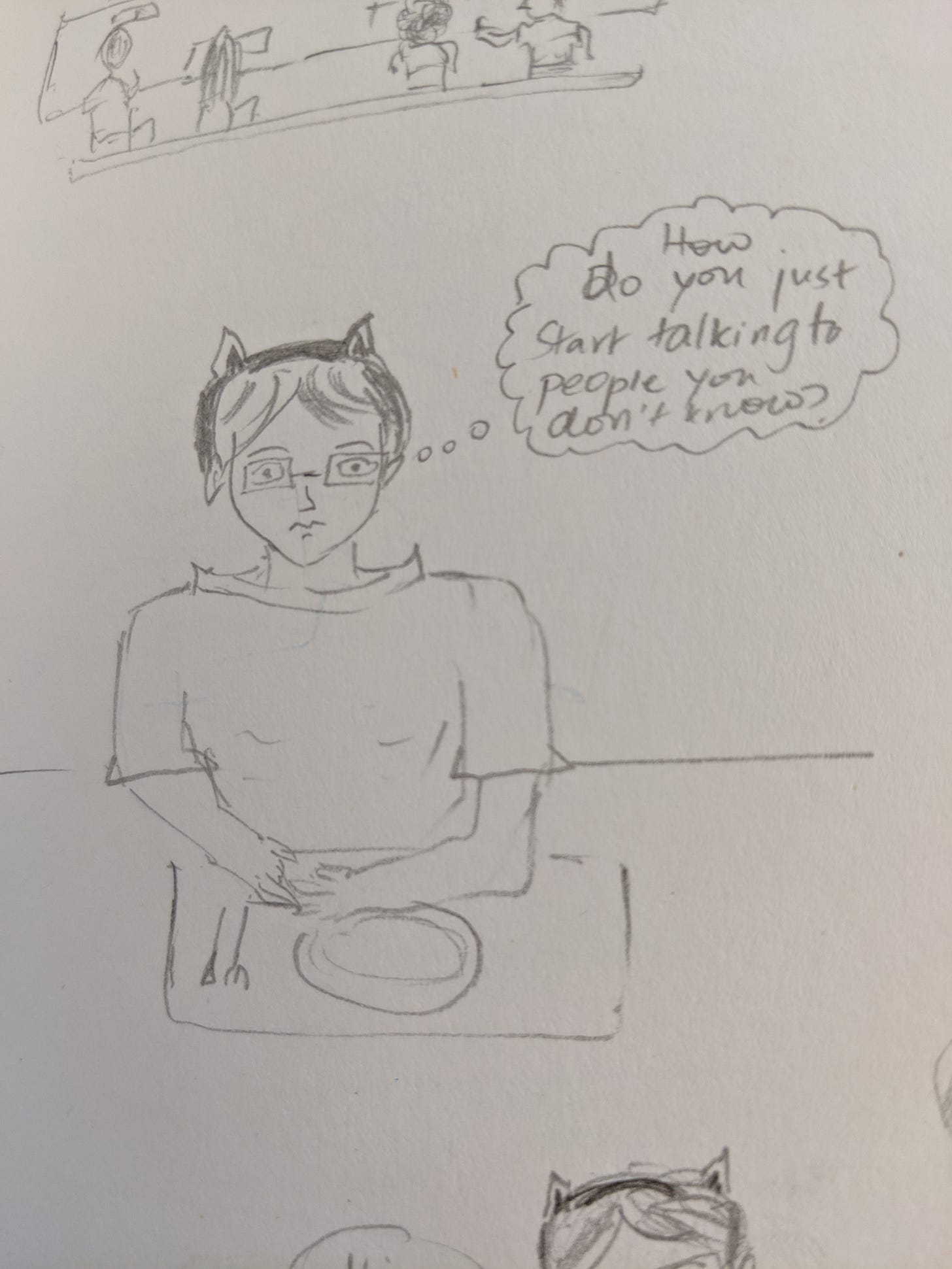

If you’d told me ten years ago that I would be able to (a) tell people nice things without stammering awkwardly (b) initiate conversations about my writing with strangers, or (c) send an important email in five minutes without scrutinizing every word a dozen times, I’d have laughed in your face. As a reference, below is a self-portrait I did when I was sixteen, back when I thought I could draw. I kept this because it’s a good reminder that no matter how other people see you, there’s always a chasm between that and how you see yourself. In my mind, I’m still this girl, with the bewildered expression and the downturned mouth, hiding behind a cat-ear hairband and glasses.

We all have things we find difficult. Those who know me at work are sometimes surprised that I’m actually deeply introverted and painfully shy of strangers. But I’m also adept at the mental gymnastics needed to put yourself in challenging situations. I’m good at game face. Because the first thing you learn as a competitive athlete is how to play a game you know you’re likely to lose, while holding on to the belief that you can still win.

If you were a newbie on a tennis court playing Alcaraz, why would you believe you had any shot of victory? But if you play with the certainty of loss, you make that loss reality. You have to have hope, however outlandish, that victory is possible.

Here is the lineup of one of the many incredible panels at Harrogate, this one focused on the domestic thriller — talking about horrific husbands and nosy neighbors. (Yes, that’s Kia Abdullah up there, go read her books!)

What is the fascination with crime and thriller? Attica Locke, who headlined yesterday’s event, talked about how these frequently disparaged “genre” novels are actually key to understanding societal values and morals. Who do we think is worthy of redemption? Who do we reward and punish? Attica talked openly about her discomfort with cops, as a Black woman, and the strangeness of having a cop admire her writing because he saw himself in the tensions and dilemmas faced by Texas Ranger Darren Mathews, in the Highway 59 series. Books are truly democratic, Attica says, because the servant and the king are both granted depth and perspective, forcing the reader to empathize with them and change their own perspective.

“Sure, hope was too often offered instead of real change, a cheap placeholder for a better day. But it also kept people alive. You couldn’t grow a tomato, a sweet pepper, or a peach without hope. You had to believe the land you were on could bear fruit to bother trying. You had to have vision to eat.”

— Attica Locke, Guide me Home

At work, I pull myself out of introversion because the work needs to be done. Certainty of purpose grants us the courage we need. When it comes to writing, Attica talked about how one of her screenwriting projects was not greenlit because there was “no market for her work internationally,” which was necessary to secure funding. She was devastated; she heard it as the rejection of her voice and her stories, but kept writing anyway. She says her ancestors’ stories demanded to be told, working their way through her blood. She couched that in “California woo-woo” but I’m not so sure it is. Where do we store our memories, if not in our bodies? And what are stories, but the expression of ancestral, primal fear?

So what keeps us writing, when the world says no? What gives us the courage to meet new people, when our bodies express the fear of rejection they have learned over generations as "shyness” or “introversion”? What else, but hope, which is the key to all survival?

This is so good / I needed it so much / huzzah and more ketchup for the home fries / perhaps there will be a pepper in the garden today

What a magical morning you had!!:)

(Also, I wish I’d known you when you had cat-ear headbands).